Political violence in America has grown louder, more visible, and more personal.

High-profile attacks and threats have become more common in recent years, raising alarms about the growing divide in American public life. Political opponents are now being viewed not just as rivals, but as enemies. This shift has left many wondering what it will take to prevent more violence, or if that is even possible.

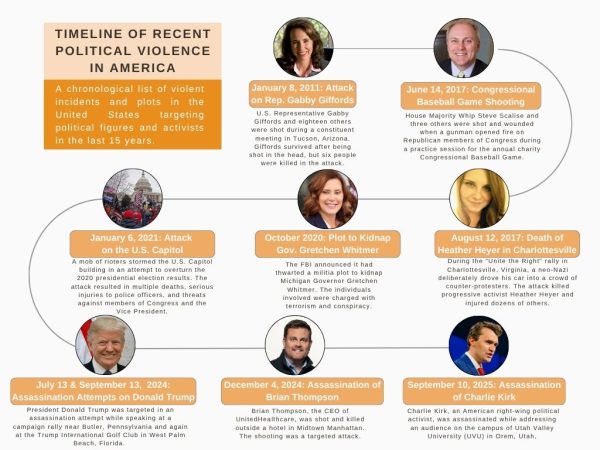

The assassination of conservative political commentator Charlie Kirk marked a new chapter in the nation’s political unrest. Though shocking to many, the event followed a troubling pattern. In just the last three years, political figures across the country have been attacked in their homes, at official events, and while conducting public business.

In October of 2022, Paul Pelosi suffered a fractured skull in an attack that was aimed at then-Speaker Nancy Pelosi. In April of 2025, Governor Josh Shapiro’s residence was set on fire while his family was asleep. In May, two Israeli diplomats were murdered in Washington, DC. The shooter claimed he was acting in retaliation for Israel’s military actions in Gaza. In June, Minnesota state representatives John and Yvette Hoffman were shot in their home. Days later, Speaker of the House Melissa Hortman and her husband were found murdered by the same attacker: a hit list of 45 Democratic officials written by the gunman was found during the investigation.

These incidents are just a few examples in a disturbing trend that many say reflects the direction of the country’s political discourse.

Some see echoes of the 1960s in today’s unrest. A time marked by assassinations, mass protests, and deep national divides. Many of the same issues—race, war, gender, and rights—still fuel today’s political conflict.

Social studies teacher Adam Gorell said the United States has a long history of bitter divisions.

“We are no less or more divided as a country than we were during the debates over the content of our constitution, or when a majority of the country thought people of color should not be citizens, or when women still lacked the right to vote,” he said.

In the last 40 years or so, the increased availability of firearms and the rise of untreated mental health crises, especially in young men, have changed the scale of that violence. Add in social media and a lack of trust, and you get what we’re seeing today. Senior Isabella Cervantes said witnessing Kirk’s killing was traumatizing.

“My initial response was shock, because I sadly was one of the people who saw it on Instagram,” she said. “ I felt vulnerable. Like, wow, someone’s life was on the line. That’s really traumatizing.”

She says the event changed how she views American politics.

One of the most dangerous shifts has been in political rhetoric. Experts say that, in the past, both major political parties provided a kind of barrier, discouraging extreme views and reinforcing democracy. But in recent decades, those barriers have weakened.

“While political violence should largely be condemned, we should also not be surprised when violent rhetoric inspires violent reprisals.” said Gorell.

Today’s modern communication has expanded the reach of extreme beliefs and conspiracies.

Americans are increasingly viewing political opponents not just as individuals with differing views, but as threats to the U.S.

“Political polarization is always dangerous,” Northwestern Historian Kevin Boyle said in an interview with PBS, “but what we’re seeing now is people in the mainstream treating each other like enemies. That opens the door to more violence.”

This environment has put pressure on political leaders to address the tone and direction of national conversations. Following Charlie Kirk’s assassination, Utah Gov. Spencer Cox took the national stage with a clear message: “Disagree better.”

In an interview on 60 Minutes, Cox, a Republican, emphasized the need to tone down political language and find ways to communicate across differences.

“Keep your values. Communicate. Find common ground,” Cox said. “We need more architects, fewer arsonists.”

These calls for unity are often dismissed as naive, especially when threats and attacks are still happening.

But Cox and others argue that naivety has always played a role in progress.

“The founding fathers were naive. Civil rights leaders were naive,” Cox said. “But hope and determination created change.”

He also reminded the public that the American flag is a symbol of collective progress, not political ownership.

“It represents 250 years of struggle. It represents all of us, not just one identity,” Cox said.

As for whether the country can pivot directions quickly or if this’ll take generations, few are optimistic about a short-term fix. Still, some believe a shift is possible, but only if citizens and leaders commit to civil discourse, reject violent rhetoric, and speak out against extremism on both sides.

Students, teachers, and citizens across the country are feeling the effects. Some worry about expressing opinions, while others are calling for more respectful dialogue. But many agree that the country is at a turning point, including Hunter Kozak, who identifies as a liberal and witnessed the Kirk assassination in person. Kozak was interviewed by 60 Minutes because he was the individual speaking to Kirk at the time of the assassination.

“Part of living in a society is not resorting to violence,” Kozak said. “Charlie Kirk’s shooter is one in 400 million. They don’t speak for us.”

As the nation reflects on recent attacks and an increasingly hostile political climate, the message from leaders like Cox is clear: change starts not with silencing each other, but with listening.

Disagree Better.